There are hundreds of memories from my childhood that stay with me and never fade or leave. One such memory was in my ninth summer, eagerly waiting for the day in October I would emerge into a double-digit age, so this is partly why I remember the June events in 1989.

Who could forget that summer when a Chinese man boldly stepped onto Tiananmen Square with grocery bags in his hand to face down army tanks?

At the time I knew nothing of the political turmoil raging across the Communist world, but as a small boy I knew one thing for certain about the situation: a man who stands in front of army tanks is very brave. He seemed to say to me and to the world that he has a right to be there, the army tanks have a right to be there, but the tanks did not have a right to harm him by going forward. It was with this simple logic that I formed much of my later adult beliefs and morals. Every person has a right to live and exist peacefully in this world, but no one has the right to harm others.

Five months later, after my tenth birthday, the Berlin Wall fell on November 4, 1989. As I watched the images of Germans hacking pieces of the twenty-eight-year-old wall off and climbing over to be reunited with loved ones, I believed the world was changing for the better, that history was being made. I was grateful to see such beautiful progress in the lives of strangers. I suppose it was then I longed to travel and explore these places unknown to me.

And on the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protest in China I found myself in Hong Kong. I arrived on June 1st for my employment at a local university and I had no immediate connections with those childhood memories and the events that would unfold before me, taking me in its warm embrace as I followed the Universe from one moment to the next throughout the day of June 4, 2014.

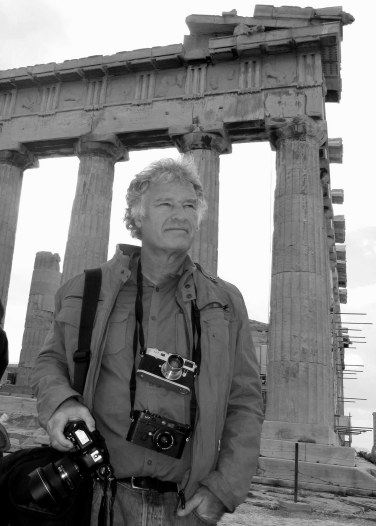

After a meeting at City University of Hong Kong, I meandered down the halls and to the main lobby where photographs were being displayed. I had seen an older man and video crew there earlier that morning but knew nothing of the man or the event. As I went to the concession stand for juice, I noticed the older gentleman once more. Gray-haired and in casual shirt and jeans, nothing too fancy or extraordinary, he blended in quite well with the students and professors from the university who gathered around the pictures posted on large white boards and chattered quietly to one another. I walked over and entered into the conversation the older man was having with another stranger, but I slipped in and listened as they discussed music.

Then it happened.

Jeff Widener, the gray-haired man I had seen earlier that morning, introduced himself and I knew he was the cause for all this commotion. And as I looked around the room, listening to him describe when and where he was at during certain moments each photograph was taken, I realized that he was the man behind the Tiananmen Square photograph. Jeff had taken the very picture of the moment that helped shape much of who I am today. And to top it all off, I was going to listen to Jeff speak about the events leading up to that shot in another ten minutes.

The crowd of students and professors from all over Hong Kong gathered in a slanted auditorium at City University that afternoon with an air of humility hovering over them. Silence seemed to take the lead just ahead of everyone as they took to their seats and waited for the panel to convene. Five minutes into Jeff’s speech I was lost in amazement and then understood I should be taking notes. This moment had to be shared, just the way his photograph slipped out of China and found its way across every major newspaper and news channel in June of 1989.

But this was 2014, 25 years later, and the crowd anxiously waited as Jeff Widener leaned close to the podium and began to tell us of the event that help shape the modern world.

Jeff bolted out with firm confirmation, “This did happen!”

After five years in Vietnam, I was not use to such direct language, and I had not expected it in Hong Kong.

He told us of the night before the photograph was taken. Riots raged across the city. Mobs attacked and killed soldiers. Soldiers attacked and killed tourists and journalists and students. Cars burned.

At one point, he raised his camera to take a picture and a rock smashed into the camera and the side of his head. The flash was ruined, and he told us how that probably saved his life. A few minutes later after being hit with the rock, he saw a soldier step down from the back of a burning armored car. The soldier’s arms were raised. A fellow soldier lay dead some yards from Jeff’s feet. An angry mob then began to beat the soldier that had his arms held over his face and head. Jeff did not think that soldier survived.

Later that night, Jeff ran through an alley, as he explained, “like a scared school girl” who was about to be killed. He made his way back to the hotel with a concussion. Safe in his room he ordered a cheeseburger and sat on the bed watching on television the riots that were happening at that very moment just outside his hotel. He said that he was “too scared and too injured to go out.”

He said the events did happen and that anyone who says different is “not following the truth.”

The day of the photo: Jeff told the audience how secret police used electric cattle prods on journalists. And when he went to the hotel a friend of his told him how police just moments before had dragged away the corpses of tourists. From the balcony, Jeff would take the iconic photo overlooking Tiananmen Square, and he thought he had missed the shot. The next morning telegrams and messages from around the world told him how his shot had made history. One UK paper used the photo for half of the front page.

Ten years later, Jeff was online looking through AOL’s most iconic collection of photographs from the last 100 years (somehow that sounds very familiar). In this collection was his photo from Tiananmen Square. He told us how it hit him “like a bolt of lightning” and it was then he knew “he did something special.”

“Fate has a strange sense of humor,” Jeff told us. He met his wife on a rainy night at a café a year later while in China and, for him, it was a happy ending.

Next, Joseph Cheng took to the podium. Joseph, a man in his more mature years but with quiet nobility in his wrinkles, spoke to us of the free protest marches in late May and early June of 1989.

He said, “We didn’t want to forget about June fourth because we are sympathetic for the students in Tiananmen Square at the time because we would also like to seek a reversal verdict, statement related to dignity and basic human rights.” Adamantly, he continued, “We refuse to be told, and refuse to accept, false information…We want to be able to speak up.”

Jeff’s and Joseph’s speech centered on the protection of Truth and how truly special such an idea can be.

That evening, June 4, 2014, I went back to a hostel I was staying at and changed in to more comfortable clothes and took the MTR to Hong Kong Island. I emerged from the subway tunnel in Causeway Bay to massive protests on the street. Men standing and seated on platforms shouted through megaphones and attached loud speakers.

At one point on the walkway, twenty police officers surrounded a man inside an elaborate creation of a cardboard army tank. I stepped quietly by and made my way to Victoria Park.

The time was roughly five in the afternoon and except for the stalls set up for organizations protesting their individual causes, the park was empty and quite peaceful, just as it might be on any Sunday of any week. I took the time to take some pictures, found a concession stand, had a can of Blue Girl and bought a bottle of water, and soon seated myself in the shade next to an old man eating his evening meal of rice and grilled chicken. Occasionally the old man scooped some rice from the Styrofoam take-away box and fed the pigeons that gathered at his feet.

At 6:30, I got up from my place by the fountain and headed to the main location of that night’s event: the Candle lighting service. CNN was set up at one corner. Reporters from around the world were interviewing students who seated themselves and waited the coming ceremony. Organizations handed out boxes of white candles and pamphlets.

I walked to a quiet area situated between the tennis courts where thousands of people were sitting and found an opening for a seat beneath a grove of trees. By 7:30 I was trapped and I looked around to find that security had locked me and the crowd into the area. Due to the excessive size of the crowd no one was getting in or out.

At one point, near the end of the ceremony, solemn men were beating drums and soon I found my own heart matching its rhythm. The beating grew slower and slower as if it were to match a man’s dying heart. Then as if all life had ceased the beating grew and revived. As the announcer repeated a phrase the masses raised their candles in honor and respect. I bowed my head and did the same.

By 9 pm I snuck quietly out of the vigil and heard one announcer shout over the microphone, “You can’t kill us all!”

He was right, but some men in this world, I was sure, would try.

I walked back to the MTR and to my room for the night where I had a beer with a friend and we talked of the night, of lost loves, and of how strange it was for us to be crossing paths at that moment.

Somehow the Universe had found the nine-year-old boy as a man, and once more I was extremely humbled and grateful to see how truly great men can be in such a devastatingly ordinary and Draconian world.

Hello, just wanted to mention, I liked this article.

It was practical. Keep on posting!